On Dying Dreams, AND WHY THEY MATTER.

Earlier this year, my friend Natalie asked me to write a guest post for her blog Natalie Said So. I had been kicking around this idea for an essay on my relationship to music and how it had shaped so much of my life and my identity - for better or worse. I was grateful to get a chance to work with Natalie to explore this idea, and thankful that she would allow me to occupy her corner of the internet for a while.

When the dream finally died, I was on the floor of my parents’ bathroom. If the tile floor in front of a jacuzzi tub in the suburbs seems like a bad choice for a life-altering flameout to you, know that you are not alone. Death, however, in its many forms is rarely as poetic as we’d like.

In the decade leading up to this point, every waking moment of my life had been devoted to the singular pursuit of music. I was a songwriter. Or, I was a songwriter. I didn’t know anymore. What I think I had known deep down, and what I was finally realizing in that moment, was that whatever I was doing wasn’t working.

I wrote my first song when I was 15 years old, sitting in the middle row of an auto shop class at Fayette County High School in Fayetteville, Georgia. It was the kind of class that attracted high-school level riffraff, and I’d been listening to the burnouts in the row behind me trading stories about how they’d finally gotten busted sneaking out to drink stolen Bud Lights behind the gas station, and I thought the story was a cautionary tale worth immortalizing into a few adolescent pop-punk stanzas that I would accompany with a choppy melody and four or five power chords. By 15-year-old christian rock standards, the song was fine - maybe even good (it’s a low bar) - but the end result wasn’t important. In that moment, I became something.

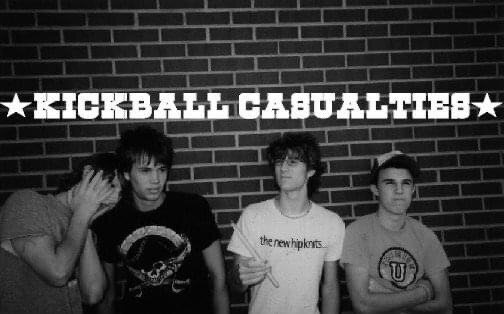

While most teenagers spend high school searching for an identity, and college searching for a purpose - both were set for me in that classroom that day. My friends and I had started a band a few weeks prior and were using our very limited skillset to approximate Ramones and MXPX songs in the youth hall at our Baptist church a few times a week. We hadn’t played any shows, and until then we didn’t have any original songs. We debuted that song, which for reasons of teenage logic we named “Fredness,” at our first live performance - a meeting of an evangelical christian club called First Priority at a local middle school. I honestly don’t remember how it went. I think there’s a video somewhere. I hope I never see it.

The band would eventually do what high school bands do, and in the meantime, I began to discover the world of solo songwriters. An especially emotional kid, I had been absolutely wrecked by Ryan Adams’ Love is Hell after my first real breakup, and I loved it. I discovered for the first time how much of yourself you could pour into art, and how that vulnerability could connect you to a new world by ripping you to pieces in front of friends and strangers, and how that allowed you all to piece yourselves back together. For better or worse, this 17-year-old discovery would dictate the trajectory of the next decade of my life.

There are a lot of stories that fill in the ten years that followed. I moved to Atlanta, went to college, played shows, wrote songs, made records, opened for bands I loved, met my heroes, got a degree, worked some dead-end jobs, made a lot of friends, and never made any money,

At some point, I met a girl. We were at a local show supporting a mutual friend’s new band and over the course of two whiskey gingers, we changed each other’s lives forever.

About a year into our relationship, I convinced Asheton to move to Nashville with me. I’d done well enough in the Atlanta music scene that it felt like the right thing to do - I could get closer to the action, find a wider community of like-minded people, maybe make something closer to a career. It seemed like it was going the ways these things go before other people start to tell your story. I’d played in a band with my friends in the suburbs, moved to Atlanta to toil for a decade in its scene, and now I was graduating to Music City to make my mark in its thriving indie community. Other friends had made the jump to Nashville or else decamped for New York or Los Angeles in furtherance of The Dream and it felt like my turn.

To her credit, Asheton was all in from day one. She found a job working for a Russian wedding dress designer and on New Year’s Day 2014, we moved into our 600 square foot apartment across from Belmont University to begin our new life.

It was idyllic, in a way. Our apartment was beautiful - a third-floor walkup in a hundred-year-old brick building with a balcony that looked onto a courtyard you’d expect to find in an older city. It was verdant in the spring and summer and reflectively melancholy when the leaves fell from the trees and the old chapel across the street showed through the branches in the winter. Most mornings, while Asheton was at work, I would sit with my guitar and write - picking out a melody or tweaking a lyric in order to get it just so. Some days I was successful, other days would end with me fending off my imposter syndrome by reading a novel on our balcony or else binge-watching Breaking Bad until she came home. To supplement our income I found work behind a desk at the Frist Center, Nashville’s non-collecting art museum, where I would occasionally get the chance to chat up Marty Stuart or T-Bone Burnett - people who were famous to people like me. We fell in with a group of people who understood us. The songwriter and his muse.

Or, the artist and his patron. Whichever.

The album I was working on when I met Asheton finally released the month after we got married. I had secured a manager and a booking agent and was releasing the record through a very small but still real indie record label based in Portland, Oregon. At times it felt like after more than a decade of work, it was finally starting to come together.

Except that it kind of wasn’t.

The record was released on CD and digital, and the tours I did to support it were mostly solo - playing whatever college or bar in the middle of nowhere would have me. It was hardly the wave of support I was hoping for, and in the best of times, I would make enough money in my two weeks on the road to cover my trip and hopefully my portion of the rent for the month. I had been married for a month or two and had spent half that time by myself in a Dodge Durango driving through rural Pennsylvania or Ohio. I was chasing the dream through the very unlikeliest of places, and it mostly eluded me.

This isn’t to say that I, or the music, wasn’t received well. The people who showed up were almost always incredibly kind and supportive. I was only booed once that I can remember - when I refused a very drunk bar patron in Appleton, Wisconsin’s request to play Wagon Wheel. But in order to sustain a life as a touring musician, you need a critical mass of fans who are willing to give you money to continue to follow your dream - and that’s hard to do when you’re playing Ohio Christian College on a Tuesday to ten people.

There were a few interviews and reviews in some super niche music blogs on the far corners of the internet. But no Pitchforks or Rolling Stones came calling. There was never a high-powered A&R guy at the back of the show. No aging legend to take me under her wing. The whole experience was kind of a letdown.

Nothing I’m saying is news to anyone reading this who has worked or is working on a career in music. And although some are surely bristling at my youthful expectations and exasperation at their inevitable nonfulfillment, I actually don’t want to discount the experience. “The Dream,” as it’s understood in the zeitgeist, very rarely works out the way most people think. What actually happens more often than not is that the dream shifts the farther into it you crawl. What starts out in some as a starry-eyed fantasy of fortune and fame typically lands in a desire to make a steady living doing something you love. There are plenty of roads to this outcome but even for a talented musician or writer the only thing that I’ve seen that yields a reliably steady living writing songs or playing guitar is time. Even still, for every breakout hit who climbs out of the clubs to sell out theaters and arenas, there are a thousand of us toiling in writer’s rooms or making coffee at 35.

Shortly after I moved to Nashville, I had lunch with a friend. He was well-established in town as both a performer and writer, and had a steady career, but hadn’t achieved the kind of breakout success that any artist hopes for. Still, by any measure, you’d call his career a success. By the time I got there, he’d been in Nashville for ten years.

“It’s a five-year town,” he told me. It was the first time I’d heard that.

For the uninitiated, conventional Music City wisdom at the time was that it took five years of meetings, writer’s rounds, and co-writes to amass the kind of network you need in Nashville in order to become successful. Last year, Hailey Whitters released a brilliant song called Ten Year Town as the opener to her equally brilliant album The Dream, so it seems the timeline has shifted in my absence.

In any event, I’ll never know how accurate he was, or she is, because I only made it two years.

The pursuit of art as commerce is an inherently selfish act. It demands a level of support from those around you that by nature you are unable to fully reciprocate. The burdens of these pursuits invariably weigh heaviest on those closest to you, if you can keep anyone close. For a struggling artist, the strain on your loved ones comes from all angles. It’s nearly impossible to make any steady money, so the bulk of the financial burden shifts to your partner. Any job you do have is unsteady and usually in the service sector - so your schedules very rarely line up. As a touring artist, you can be on the road anywhere from three days to six weeks at a time - and as a special kind of wrench into your relational gears, that number generally grows with your level of success. So if you’re fortunate enough to be able to draw crowds everywhere in the country, you can look forward to two or three months on the road at a time. And none of this takes into account the fact that as an artist your job is essentially to create a brand out of yourself, so there’s a healthy bit of ego involved in the whole thing.

By the end of 2015, Asheton and I were burning the candle at both ends. She was working a customer service job at a ‘cool’ company that used periodic open bar tabs and the preponderance of office snacks as an excuse not to pay a living wage, and I was driving around the country by myself playing burrito shops on the Jersey Shore five nights a week. She got an offer to work at an advertising agency back in Atlanta, and we made the tough decision to move back to our hometown. I was mostly touring, very rarely co-writing, and my team was scattered around the country. I could do what I was doing from anywhere. She had followed me to Nashville so that I could build my dreams, and I owed it to her to give her the same courtesy.

I’ll save you the details of what comes next as they aren’t mine to fully tell. The basics of it are that the job turned out to not be what we thought, and it brought with it a crisis we weren’t prepared to deal with.

The long and short of it is that there was a time within the first few months of 2016 where we checked our joint bank account a few days after payday to find that we had three dollars between us.

The dream was dying.

I believe that poverty in the support of something worthwhile is noble. It teaches you how to live without - about the difference between what we value in our society and what’s important. I also realize that this is a privileged viewpoint and that not everyone has the opportunity to choose between relative poverty and relative abundance. I was able to choose this path because of the abundance of safety nets around me, and I know that. It’s still jarring, however, to realize that in order to buy a Quarter Pounder meal to split with your wife you’d need to borrow money.

Eventually, everything would come to a head. We were living in my parents’ house in the suburbs of Atlanta, looking for a place of our own, and we had nothing. I had woken up every morning of my life since I was 15 years old knowing exactly what I was put on Earth to do, and I had done nothing else for the next 15 years. My identity, who I knew myself to be and who I allowed others to perceive me as, were inextricably bound to the idea that I was a musician. I was proud of the fact that while some had quit to pursue what I saw as an easier path, I had stayed true to myself. I was the rare true believer. An artist. Anything to keep from seeing myself as what I increasingly believed myself to be.

A failure.

If I wasn’t a musician, what was I? Who? I used to get a kick out of answering the question when anyone asked what I did for a living. I was a musician. How interesting! What a life! Never mind that I could have just as easily answered the question by saying that I sat around playing acoustic guitar while my wife paid the bills. The identity was worth more to me than almost anything.

Thankfully, I was smart enough to figure out that it wasn’t worth more than my marriage.

Somewhere deep inside me, I knew it wasn’t fair for me to ask Asheton to carry that burden by herself anymore. Still, it took that moment in the floor of a bathroom in Fayetteville, Georgia - the moment where my wife, who had married me less than a year prior, looked me in the eye and told me something I knew in my heart but had refused to acknowledge.

She told me that I was miserable.

The moment she said it, I began to weep. In naming it, she’d broken through a wall that I’d been building for years. I cried for myself and for my family, both in mourning for what I’d lost and in gratitude for what we could start to build. In that moment I finally agreed to give more than I took, and acquiesce to the reality that our life together was so much more than my attempt to satiate my ego.

I think I did one last tour before I parted ways with my booking agent. I got sick midway through the trip and by the last night, I couldn’t sing a note. I had to cancel the last show, and I drove home.

This is how the world ends.

I started looking for a ‘real’ job and wound up working for the State of Georgia. It wasn’t anything like what I could describe as a dream job, but it allowed me to start to realize that I could survive - and possibly even be happy - without the part of myself I had always assumed was the crucial bit.

You could massage this story into ending right here. I often do. Asheton and I are still married, and we have an incredible three-year-old daughter who has given us both (me especially) a much-needed new perspective on what we truly value. We are happy and healthy. I feel lucky.

But in truth, I still lost something important that day.

I lost music.

I’m sure everyone is wired for different reactions to giving up a piece of themselves - but when I gave up on The Dream, I couldn’t even listen to music. I walked away from every song or album that had inspired me to write. I didn’t go to shows or listen to records or roll my windows down when the temperature hit 70 and lose myself in a great song as the highway wind whipped around me. I couldn’t hear art or feel myself opening to greater truths through songs like I did before. I could only see the technical stuff - what word went where and what I would have written differently. I wondered why certain artists got the chance to break through while I was stuck in an office building writing a logistics newsletter that no one read.

So instead I listened to podcasts and sports radio. When I started that first office job, I didn’t take the time to dive deeper into that creative energy that had sustained me all those years. Instead, I devoted one of the two screens on my desk to playing The Office on a loop in the background. Just noise to drown out the part of me that was mad at itself for giving up.

I like to think of it sometimes as if I’m a baseball player who spent his whole life preparing for the Major Leagues, just for his career to fizzle out in Triple-A. I wonder if that player can still love the game like he used to when he sees the teammates he spent hours working alongside getting their cracks at the big stage. Is he proud of them when they get their first hits? First home runs? Or does he have to turn away because someone else is living the dream he worked his whole life for.

When he goes home, is he still proud?

It’s been six years since my last album was released. Oddly enough, thanks to the algorithm and a fortuitous early placement on Starbucks in-store playlists, it still gets a decent amount of play around the world. It’s not enough to make me think I can get back to it, but it’s a nice reminder that it happened, and that someone else connected to it in the same ways that I did. I’ve put enough distance between myself and my past life that I can begin to look at that part of my life as a part of my life instead of the gravity that pulled the rest of it into orbit. I look fondly on the stories I have from the weird and wonderful places that kind of life can take you, and I feel grateful for the ability to be around for my kid as she grows up. Truthfully, I can’t imagine willingly leaving my family at home for 6 weeks or more at a time. I mourn for my friends who have had to miss first words and first steps like I used to mourn the loss of my creative life.

A few months ago I, like a lot of people this year, was laid off from a job I had been doing for the past two years. It wasn’t entirely unexpected, but it was devastating. It felt like the first time that girl broke my heart almost two decades ago. It was betrayal and an uncertain future and rage all wrapped up into one tidy package. Naturally or unnaturally, I responded in the same way I had twenty years ago.

I picked up my guitar and started to play.

I didn’t sit down to write a song with the pressure of making something that could make me money, or fit neatly into a record. I just sat and played and sang. I worked my way through some old tunes and slid into that wonderful melancholy that a good song always holds within itself. If you’ve been there, you know the feeling. It’s an all-encompassing sadness that connects you to something bigger. Suddenly, the empty feeling is replaced by a knowledge that you have been here before; that others have come before you and still others will follow. You are tapped into an energy that tells you plainly what it has always been there to say. That you are not alone.

I didn’t decide in that moment to be a Musician again. This isn’t the part of the story where I write twelve songs in some early-middle-aged dramatic fever dream that catapults me to Sturgill Simpson levels of notoriety. And after that moment, I put my guitar away where it’s mostly been since. But it is where it is and I am where I am and from time to time maybe our paths will cross. We’re not avoiding each other anymore.

A few days after I was fired, I put my kid to bed and headed upstairs to get a workout in and clear my head. In a bit of thirty-something wistfulness and regression, I had spent much of my newfound free time that day skateboarding, and I needed to flush out my legs, or else the likelihood that I’d be able to walk that weekend was low. I hopped onto the wifi-enabled exercise bike I could suddenly no longer afford to own and chose a twenty-minute‘ recovery ride’. I turned the lights off, put my headphones in, and heard the opening bars to Phil Collins’ In the Air Tonight. I know it’s a cliche music moment, but that may be part of why it happened - when the drums came in, I found myself completely transported. The playlist eventually found its way to Bon Iver’s The Wolves (Act I and II) from the For Emma, Forever Ago record.

The first lyrics to that song brought me back into that familiar fold - the feeling of being known by something bigger than myself:

“Someday my pain

Someday my pain will mark you…”

And the ending reminded me, all these years later, that it was ok to mourn. That maybe I didn’t ever fully mourn that loss of something I really did love. And that it was ok to have loved something that couldn’t ever love me back in the way that I needed it to. When he sings the refrain over and over again, “What might have been lost…” as the instrumentation devolves into cacophony - unhinged and untethered - my body remembered what my mind had tried so hard to get rid of. Despite the disappointment I felt, and still sometimes feel, about my career as a musician - I didn’t make a choice to connect to songwriting in the way that I did. It happened because it had to happen just like it ended because it needed to end. I don’t know that I’ll ever recreate that singularly focused Sense of Purpose - but I also don’t really know that I need to.

When it was first making the rounds a few weeks ago, I pulled up the video of The Linda Lindas’ Racist, Sexist Boy on my laptop so I could see for myself the tween punk band who was lighting up all the music blogs. As soon as the band launched into the first chords of the song, my daughter ran over to me to see what was happening. She crawled up into my lap and sat, rapt, and watched as the four tween-to-teenage girls ripped through a minute and a half of taking their power back on their own terms. She was beaming. She clapped when the song was over and demanded we watch the rest of the concert. We sat that morning and watched every single piece of video content available from The Linda Lindas. If you’ve ever met a three-year-old, you know that paying this much attention to anything that isn’t PAW Patrol is a rare occurrence.

Since that moment, she has demanded to listen to The Linda Lindas every moment there is music playing anywhere. She sits in her car seat and sings along to every song, and sometimes we catch her singing to herself when she’s coloring or jumping on her trampoline.

My little girl has a favorite band.

On a recent rewatch of the LA Public Library show that spawned the band’s viral moment, my daughter pointed at the band’s guitar pedals and amps and asked me about them. I explained to her what they did and how the band was using them to make the sounds she was hearing. I told her that I had a similar setup that I used to use when I was out playing music with my band.

“Can you show me?” she asked.

As I plugged in my amplifier for the first time in years it occurred to me that maybe the dream never died. Maybe I just didn’t understand it until now.